(continued) The Mechanics of a Mosquito

Life Cycle and Breeding

Mosquitoes hatch from eggs and go through several stages in their life cycle before becoming adults. Most females lay their eggs in water and the larva and pupa stages live entirely in water. When the pupa change into adults, they leave the water and become free-flying land insects.(The adult, mated females of some species can survive the winter in cool, damp places until spring, when they will lay their eggs and die.)

|

|

|

|

Photos courtesy Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and USDA/ARS (upper right)

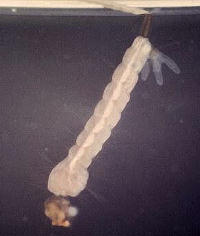

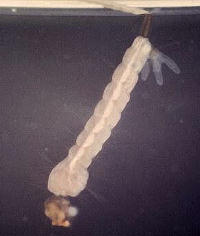

Life cycle of the yellow-fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti):

An egg (upper left) laid on the surface of the water hatches into an aquatic larva (lower left). The larva changes into an aquatic pupa (lower right), which then changes into a free-flying adult (upper right). The adult female bites a human to gather blood for laying eggs.

|

Most mosquitoes lay eggs in water, which can include large bodies of water, standing water (like swimming pools) or areas of collected standing water (like tree holes or gutters). Females lay their eggs on the surface of the water, except for Aedes mosquitoes, which lay their eggs above water in protected areas that eventually flood. The eggs can be laid singly or as a group that forms a floating raft of mosquito eggs. Most eggs can survive the winter and hatch in the spring.

Identifying Larvae

You can distinguish the larvae of various mosquito species. Anopheles larvae lie parallel to the surface of the water, while larvae of Aedes and Culex extend down into the water (the air tubes of Culex are longer than those of Aedes).

|

Mosquito eggs hatch into larvae or "

wigglers," which live at the surface of the water and breathe through an

air tube or

siphon. The larvae filter organic material through their mouth parts and grow to about 0.5 to 0.75 inches (1 to 2 cm) long; as they grow, they shed their skin (

molt) several times. Mosquito larvae can swim and dive down from the surface when disturbed

Mosquitoes are Important

The mosquito larvae and pupae are important food sources for fish in aquatic ecosystems.

|

After the fourth molt, mosquito larvae change into pupae, or "tumblers," which live in the water anywhere from one to four days depending on the water temperature and species. The pupae float at the surface and breathe through two small tubes (trumpets). Although they do not eat, pupae are quite active. At the end of the pupal stage, the pupae encase themselves and transform into adult mosquitoes.

Inside the pupal case, the pupa transforms into an adult. The adult uses air pressure to break the pupal case open, crawls to a protected area and rests while its external skeleton hardens, spreading its wings out to dry. Once this is complete, it can fly away and live on the land.

One of the first things that adult mosquitoes do is seek a mate, mate and then feed. Male mosquitoes have short mouth parts and feed on plant nectar. In contrast, female mosquitoes have a long proboscis that they use to bite animals and humans and feed on their blood (the blood provides proteins that the females need to lay eggs). After they feed, females lay their eggs (many need a blood meal each time they lay eggs). Females continue this cycle and live anywhere from many days to weeks (longer over the winter); males usually live only a few days after mating. The life cycles of mosquitoes vary with the species and environmental conditions.

As mentioned before, only female mosquitoes bite. They are attracted by several things, including heat (infrared light), light, perspiration, body odor, lactic acid and carbon dioxide. The female lands on your skin and sticks her proboscis into you (the proboscis is very sharp and thin, so you may not feel it going in). Her saliva contains proteins (anticoagulants) that prevent your blood from clotting. She sucks your blood into her abdomen (about 5 microliters per serving for an Aedes aegypti mosquito).

If the female is disturbed, she will fly away. Otherwise, she will remain until she has a full abdomen. If you were to cut the sensory nerve to her abdomen, she would keep sucking until she burst.

After she has bitten you, some saliva remains in the wound. The proteins from the saliva evoke an immune response from your body. The area swells (the bump around the bite area is called a wheal), and you itch, a response provoked by the saliva. Eventually, the swelling goes away, but the itch remains until your immune system breaks down the saliva proteins.

To treat mosquito bites, you should wash them with mild soap and water. Try to avoid scratching the bite area, even though it itches. Some anti-itch medicines such as Calamine lotion or over-the-counter cortisone creams may relieve the itching. Typically, you do not need to seek medical attention (unless you feel dizzy or nauseated, which may indicate a severe allergic reaction to the bite).

Bibliography

Mosquito: A Natural History of Our Most Persistent and Deadly Foe

-Andrew Spielman, Sc.D., and Michael D'Antonio

How a Mosquito Works-Craig C. Freudenrich, PHD

Photographer: Jim Gathany